Lights and Shadows of July 11

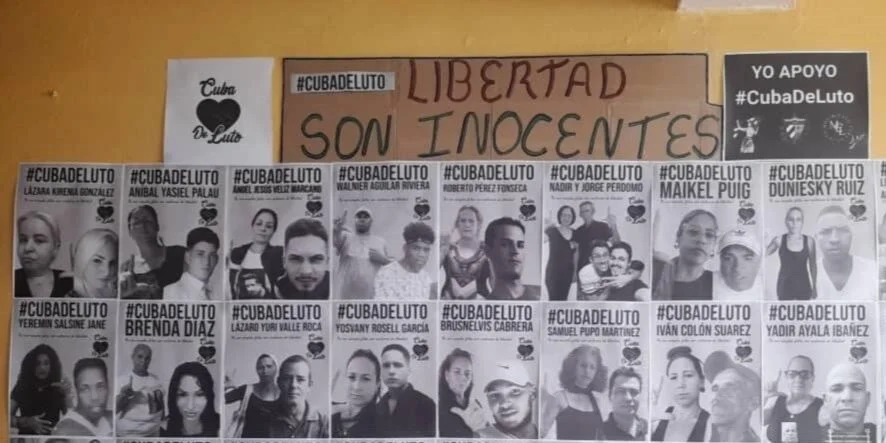

It has been four years since those women and men were deprived of their freedom due to an abuse of power—yes, by the powers of the State—and their imprisonment is unlawful.

Puerto Padre. –Friday, July 11th marked four years since the social uprising universally known as 11J. It began on Sunday, July 11, 2021, and spread across nearly the entire island. It was a massive civic protest, unprecedented since January 1, 1959, when Fulgencio Batista fled the country.

But whereas Batista’s departure prompted celebratory demonstrations that turned violent against symbols of his dictatorship—such as casinos and gaming halls in luxury hotels—in July 2021, Cubans had the courage and merit to rise up against the full force of an intact totalitarian regime. Some did so peacefully; others, as their parents and grandparents had done in 1959 with less restraint, targeted businesses owned by the military or other monopolies, including Communist Party (PCC) headquarters. It was a citizen-led protest that shook both Cuba and the world, involving people of all ages—women and men, elderly and young, some nearly children—demanding freedom and dignified living conditions. Today, hundreds of them remain imprisoned.

Under the watchful eye of the true power holder, General Raúl Castro, Miguel Díaz-Canel—Cuba’s quasi-dictator—was captured in voice and image as he committed what has been widely regarded as a crime against humanity. On July 11, as protests erupted from small towns to major cities, he declared: “We are ready for anything,” and sealed it with, “the order to fight has been given—revolutionaries, take to the streets.” That statement paved the way for unarmed protesters—men, women, and many teenagers—to be brutally attacked by army special forces and police. In some cases, repression was carried out openly; in others, by military personnel disguised as civilians—betrayed only by their boots—acting under Díaz-Canel’s orders and aided by armed communist enforcers wielding clubs. Many of these repressors have already obtained or are now seeking residency in the United States.

The word sedition first appears in the Bible, before the time of Christ. It refers to a public expression of discontent involving resistance—or the call to resist—against royal power. In modern terms, it means civil unrest, often involving violence against the established order, and is thus criminalized not only in Cuba but in many countries. However, although Díaz-Canel and his spokespersons claim that there are no political prisoners in Cuba, and even as the regime has spent the last four years downplaying the events as mere “disturbances,” the July 11 protests and those that followed do not constitute common crimes, motivated by greed or passion, as claimed by regime prosecutors. Instead, they represent, under customary law, evolutionary offenses, which, morally and scientifically speaking, are not crimes at all.

“An evolutionary offense,” writes Jiménez de Asúa in Chronicle of Crime, “is, in short, one committed for altruistic reasons, in an effort—however utopian—to hasten political and social progress.”

And since resistance and incitement to resistance are legitimate tools in the face of oppression—and because the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in its third preamble, deems it essential that individual liberties be protected so that people are not forced to resort to “rebellion against tyranny and oppression”—it is clear that the imprisonment of hundreds of Cubans is both unjust and illegal.

Those men and women have now spent four years deprived of their freedom due to an abuse of power—yes, by the powers of the State. Their imprisonment is unlawful because the July 11 protests do not constitute crimes, neither in their acts nor in their purpose. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—which Cuba not only signed but helped draft—and even eight years before the proclamation of those rights, the 1940 Cuban Constitution already stated in Article 40:

“Any governmental or legal provisions that regulate the exercise of the rights guaranteed by this Constitution shall be null and void if they diminish, restrict, or distort those rights. Appropriate resistance is legitimate to protect the individual rights previously guaranteed.”

There are women and men imprisoned in Cuba today for having taken action to protect individual rights. That—and nothing else—was what motivated the protesters, even if, during those events, there were actions resembling property damage or offenses against ownership. In essence, such acts are not crimes—even if they should not have occurred—because accusing them of theft would be like calling a soldier a thief for seizing his adversary’s position in battle.

Today, those political prisoners—specifically forgotten by their fellow citizens, who benefit from their captivity—are not only forgotten by the applauding audience of Castro-communist rhetoric, but also by those who, without fighting the regime, invoke the word dictatorship merely to flee Cuba, citing “credible fear” in their applications for political asylum. While some applaud and others escape, in the shadows of the dictatorship’s prisons, those women and men remain the light of Cuba.

ARTÍCULO DE OPINIÓN

Las opiniones expresadas en este artículo son de exclusiva responsabilidad de quien las emite y no necesariamente representan la opinión de CubaNet.

Recibe la información de CubaNet en tu celular a través de WhatsApp. Envíanos un mensaje con la palabra “CUBA” al teléfono +1 (786) 316-2072, también puedes suscribirte a nuestro boletín electrónico dando click aquí.